The success of a project can be assessed based on the hours worked or from the managerial point of view – based on the value delivered to the customer. If the customer’s business goals are met, it’s a success.

At Bart.sk, we focus on long-term projects and long-term customer goals. Completing and submitting a short project is relatively easy. Delivering a quality product perpetually and consistently over a long period of time is something that requires a different perspective on how to write and maintain code.

Code review is one of the tools for increasing the quality of your team and the code itself. It’s basically a process in which one or more people check your code before it’s incorporated into a project.

You can meet the code review as a merge request (MR) on GitLab or a pull request (PR) on GitHub. Hereafter, I use the term MR, because we work on GitLab, but it’s the same thing.

Why is code review important?

We all see our code as the best thing that we managed to cough up that day. But the truth is that if we spend a lot of time solving a specific problem, our perception of the problem may shrink and we’ll miss the broader context. For example, that our function or component solves one particular problem, but we forget to treat some inputs for which we can’t think of a use-case.

In the same way, all variables, feature names and algorithms are very clear to us. But it usually helps when someone else looks at the code and checks if it reads well. Most of the time, programmers just read the code anyway.

In our company, reviewers often try out the code themselves. For example, when it comes to an MR for a part of a UI, they can come up with improvements, and if they try to use the UI in a way the programmer didn’t intend, they will find bugs.

If you also involve QA (Quality Assurance) in a MR, you can find mistakes even at this stage, which will save you time later.

I see the main benefit of a MR in increasing code quality and reducing the number of bugs, but no less important thing is that everyone involved learns thanks to a MR. They learn to use technology, they get to know the project.

From my experience, I can tell you that everyone makes mistakes. Seniority doesn’t matter. One can still learn something new.

Code review can also be used for an internal workshop. E.g. Stano recently did a workshop where he explained to us on a relatively large MR how he migrated code to the latest Angular, commit after commit.

What a good MR looks like

It’s usually true that a MR should have an excellent name and an excellent description so that even a new teammate would be able to do a code review.

If it’s bug fixing, describe how the bug manifests, in which environment, on what account and what the exact steps to replicate it are. With a new feature, it’s great if the description includes e.g. design, specification, requirements and other specifying information. Then the reviewer can get a good overview of what they’re going to check.

Pay attention to the range as well. Personally, as a reviewer, I prefer to have ten MRs with one change to one MR with ten changes. Then I lose focus a little. In other words:

10 lines of code = 10 issues.

500 lines of code = ‘looks fine’.

Every code review

A good MR not only fixes a bug or adds a feature, but improves what’s already on the project.

In my opinion, however, the best MR is the one that takes away from the project instead of adding to it. If you fix a bug or add a feature while you’re at it, you deserve an extra plum dumpling for lunch.

How to give feedback and not be a jerk

Many times I’ve encountered the view of junior programmers that they even like their code being criticised. From my point of view, this is a great mindset where the “hunger” to learn is greater than the ego. ? But be careful not to overdo it with criticism.

The most important principle of feedback giving is – don’t be a jerk. It’s usually enough to leave your ego at home and remember what gems you once coded. Everyone learns.

At the beginning of the code review, try to absorb as much information about the code as possible. Mainly why it was created and what it has to solve.

When you start evaluating and see that your colleague, in your opinion, has written complete nonsense, take a break and don’t write the review right away. If it doesn’t work for you even after a few minutes, and you’ve already checked the circumstances of that code, write in questions or at least don’t command. Offer improvements, suggestions. ‘Do you think it would be better if you used…?’, ‘What if you tried this… algorithm’, ‘I think this could be solved this way…’ At all times, try to be objective and try to keep your emotions in check.

If you do comment, insist on a satisfactory answer. The answer should never be that ‘this is just how we do it here’ or “I copied it from the stack overflow’, or ‘we’ll fix it when it’s time’ (spoiler alert: you won’t).

For programmers, communicating with other human beings is usually the reason why they prefer to communicate with computers. However, during code review, we must restore (or find) this forgotten soft skill. Text doesn’t carry much emotion, so use emoticons and communicate your criticism. Don’t be afraid to praise your colleague, it will be appreciated.

When someone does a code review for you,

don’t take the comments personally.

As programmers, we’re artists in a way, and when we create something, we’re proud of it and it isn’t always easy to accept criticism. Especially after we’ve been working on something for hours or days. Anyway, it happens that we have errors in there or someone has a better idea or a better algorithm.

We just have to take it humbly and learn something new. Welcome criticism with open arms. Feedback, even critical, is for the good of the project, you and your customer.

To avoid criticism, do nothing, say nothing, and be nothing.

Elbert Hubbard

How long should a code review last

This is a common question even in more experienced teams. Of course, if you’re expecting to receive a specific number, you’re waiting in vain.

But try to think about what precedes the code review.

Usually, requirements are written, design is created, functional specifications and technical analysis are written and finally, programming starts.

The programmer must understand why they’re going to code something, what the context is, what the limitations, dependencies and requirements are. They usually code something, then rewrite it, find a better solution, rewrite it again and finally submit their code, which they worked on for two days, for code review.

Ask yourself, how much time do you need to understand the problem and check if the code delivers the promised value? Sometimes you even need to run the code, test it yourself and write valuable feedback. I don’t know how much time you need, but it will probably be a significant part of those two programming days.

Don’t waste time

There are many examples of how to waste time with code review. For example, you can search for missing semicolons or argue for weeks whether to use tabs or spaces, or whether to put a parenthesis in a new line or in the same one.

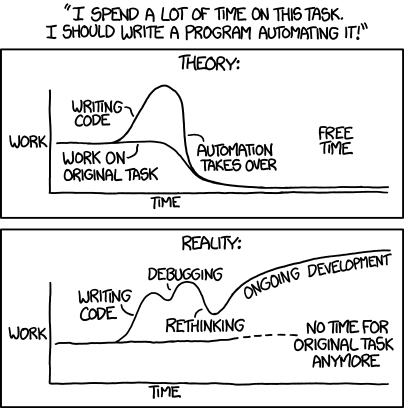

Try to fine-tune as many things as possible mechanically before the reviewer sees the code for the first time. Try to automate everything you know how to automate. But be careful not to let it slip out of your hands.

Source: https://xkcd.com/1319/

In our company, we’ve arranged this so that after each push event in the merge request (meaning in the branch from which the MR is created) a pipeline is started (more about GitLab pipelines here) where the following is checked:

- whether the code is formatted according to the agreed code style,

- whether it passes static analysis (set of rules for best practices),

- whether unit tests pass,

- whether the project can be built.

Such a “clean” MR is then checked by two people, who can now fully devote themselves to looking for errors in logic, potential bugs, bottlenecks and inconsistencies, or moaning about wrong naming of variables for at least a little while.

In the case of a MR of lower importance, one reviewer is enough.

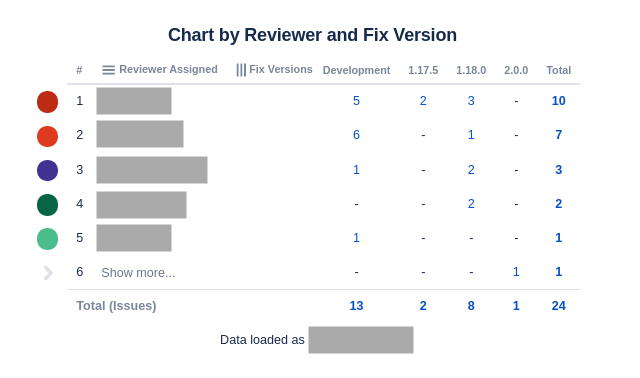

Bonus: connection with issue tracker

You can program a connection with your favourite issue tracker in a few hours and it will save the programmers hundreds of hours.

Our automated link with JIRA ensures that a link to a specific JIRA issue is added to the MR description, which describes ‘what’ and ‘why’. Programmers don’t have to write MR descriptions manually, all details, whether about a bug or a feature, are in the JIRA issue. The bonus is that issues in JIRA are automatically moved based on MR status. So the programmer doesn’t waste time on “bureaucracy”.

This connection also allows us to create tables (below), which we show on daily stand-ups – they show who has how many MRs assigned and in which version. Thanks to them, we have a quick overview of how busy we are and which MR needs to be prioritized.